- September 18, 2025

7 Expert Opinions I Agree With (That Most People Don’t)

- September 04, 2023

- in Success

Recently, I wrote a defense of the uncontroversial-within-cognitive-science-but-widely-disbelieved idea that the mind is a computer.

That post got me thinking well-nigh other ideas that are widely wonted amongst the expert communities that study them, but not among the unstipulated population.1

I well-set with some of the pursuit ideas surpassing I read much well-nigh them; for these, the expert consensus reinforced my prior worldview. But for most, I had to be persuaded. Many ideas are genuinely surprising, and one needs to be confronted with a lot of vestige surpassing waffly their mind well-nigh it.

1. Markets are mostly efficient. Most people, most of the time, cannot “beat” the market.

The efficient market hypothesis argues that the price of widely-traded securities, like stocks, reflects an team of all misogynist information well-nigh them. This ways investors can’t spot “deals” or “overpriced” resources and use that knowledge to outperform the stereotype market return (without taking on increasingly risk).

The mechanism underlying this is simple: Suppose you did have information that an windfall was mispriced. You’d be incentivized to buy or short the asset, expecting a largest return than the current market would dictate. But this whoopee causes the asset’s price to retread in the opposite direction, moving it closer to the “correct” value. Taken as a whole, the very whoopee of investors trying to write-up the market is what makes it so difficult to beat.

Asset frothing and stock market crashes are not good vestige versus this view. (Of all the people who “predicted” a bubble/crash, how many made money from their prediction?) Nor is that friend you know who seemingly made fantastic returns from crypto/real estate/penny stocks/etc. (That’s usually explained by them taking on increasingly risk, and thus having a higher risk premium, and getting lucky.)

The obvious magnitude is that for most retail investors, it’s weightier to put their money in broad-based alphabetize funds to get the benefits of diversification and earn the stereotype market return with few fees.

2. Intelligence is real, important, largely heritable, and not particularly changeable.

This is one that I fought unsuspicious for years. It goes versus my beliefs in the value of self-cultivation, practice and learning. However, the evidence is overwhelming:

- Intelligence is one of the most scientifically valid psychometric measurements (far increasingly so than personality, including the dubious Myers Briggs).

- It is positively correlated with many other things we want in life (including happiness, longevity and income!).

- It shows strong heritability, with the g-factor maybe stuff as much as 85% heritable.

- Finally, few interventions reliably modernize IQ, with a possible exception for increasingly education (although it’s not well-spoken this improves g).

I don’t like trotting this treatise out. I find it much increasingly well-flavored to believe in a world where IQ tests don’t measure anything, or they don’t measure anything important, or that any differences are due to education and environment, or that you could modernize your intelligence through nonflexible work.

That said, I do think there’s a silver lining here. While your general intelligence may not be easy to change, there’s zaftig vestige that gaining knowledge and skills improves your worthiness to do all sorts of tasks. Practically speaking, the weightier way to wilt smarter is to learn a lot of stuff and cultivate a lot of skills. Since knowledge and skills are increasingly specific than unstipulated intelligence, that may be less than we desire, but it still matters a lot.

3. Learning styles aren’t real. There’s no such thing as stuff a “kinesthetic,” “visual,” or “auditory” learner.

I’ve had multiple interviews for my book, Ultralearning, where the host asks me to talk well-nigh learning styles. And I unchangingly have to, overly so gently, explain that they don’t exist.

The theory of learning styles is an eminently testable hypothesis:

- Give people a survey or test to see what their learning style is.

- Teach the same subject in variegated ways (diagrams, verbal description, physical model) that either correspond with or go versus a person’s style.

- See whether they perform largest when teaching matches their learning style and worse when it doesn’t.

Careful experiments don’t find the performance enhancements one would expect based on the theory. Ergo, learning styles isn’t a good theory.

I think part of why this idea survives is that (a) people love the psychological equivalent of horoscopes—this may be why Myers Briggs is so popular despite a lack of scientific support for it as a theory. And, (b) that some people are simply largest at visualizing, listening or increasingly dexterous is a truism that seems quite similar to learning styles. But just considering you’re largest at basketball than math doesn’t midpoint you’ll learn calculus largest if the teacher tries to explain it in terms of three-pointers.

4. The world virtually us is explained entirely by physics.

Sean Carroll articulates a basic physicist worldview that quantum mechanics and the physics described by the Standard Model substantially explain everything virtually us.

The remaining controversies of physics, from string theory to supersymmetry, are primarily theoretical issues only relevant at extremely upper energies. For everyday life at room temperature, the physics we once know does remarkably well at making predictions.

True, knowing the Standard Model doesn’t help us predict most of the big things we superintendency about—even gingerly the effects of interactions between a few particles can be intractable. But, in principle, everything from democratic governance to the eyeful of sunsets is contained in those equations.

5. People are overweight considering they eat too much. It is moreover really nonflexible to stop.

The calorie-in, calorie-out model is, thermodynamically speaking, correct. People who are overweight would lose weight if they ate less.

Yet, this is really difficult to do. As I discuss with neuroscientist and obesity researcher Stephan Guyenet, your smart-ass has specific neural circuitry designed to stave starvation and, by extension, any rapid weight-loss. When you lose a lot of soul fat, your hunger levels increase to encourage you to bring it when up.

This is whimsically a radical view, but it’s strongly opposed by a particularly noisy segment of online opinion that either tries to explain weight in terms of something other than calories or, conceding that, seems to predicate that the problem is simply a matter of applying a little effort.

One reason I’m optimistic well-nigh the new matriculation of weight-loss drugs is simply that, as a society, we’re probably heavier than is optimally healthy, and most interventions based on willpower don’t work.

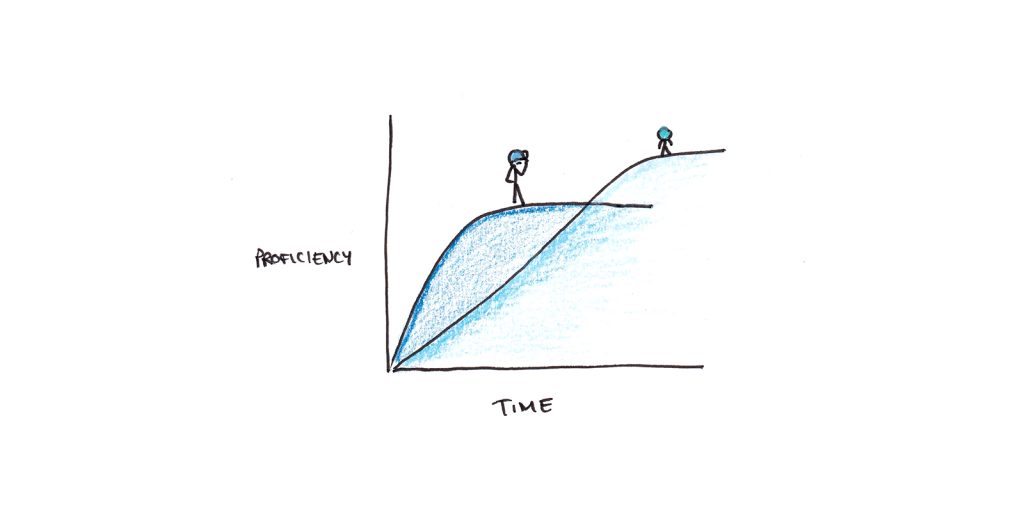

6. Children don’t learn languages faster than adults, but they do reach higher levels of mastery.

Common wisdom says if you’re going to learn a language, learn it early. Children regularly wilt fluent in their home and classroom language, indistinguishable from native speakers; adults rarely do.

But plane if children sooner surpass the attainments of adults in pronunciation and syntax, it’s not true that children learn faster. Studies routinely find that, given the same form of instruction/immersion, older learners tend to wilt proficient in a language increasingly quickly than children do—adults simply plateau at a non-native level of ability, given unfurled practice.

I take this as vestige that language learning proceeds through both a fast, explicit waterworks and a slow, implicit channel. Adults and older children may have a increasingly fully ripened fast channel, but perhaps have deficiencies in the slow waterworks that prevent completely native-like acquisition.

This implies that if you want your child to be completely bilingual, it helps to start early. But that probably requires non-trivial amounts of immersive time in the second language. If they’re only going to a weekly matriculation the way most adults learn, then there may be no special goody to starting extremely young and maybe plane an wholesomeness to starting older.

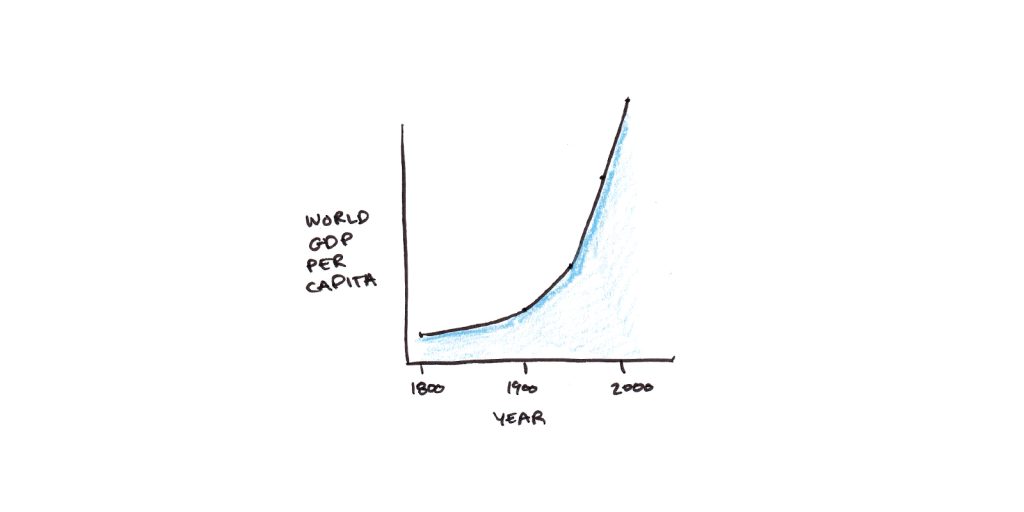

7. We’re largest off than our grandparents. We’re vastly largest off than our ancestors.

Economic pessimism is fashionable.

Everyone I talk to likes to point out various ways that the current generation (at least in North America, where I reside) has it worse than our parents did: houses and higher degrees financing forfeit more, and it is harder to support a family on a single earner’s paycheck.

But pretty much every economic indicator is positive. Plane the indicators that pessimistic pundits like to mutter well-nigh are largely from areas where wages have been stagnant, or inequality has been rising rather than genuine decline.

The world we live in today is wealthier than that of our parents, and fantastically wealthier than it was a century ago. Economic progress is not everything, but it matters a unconfined deal.

This isn’t a undeniability to stop striving and rest on our laurels; many problems in society still require fixing. But a narrative that begins by denying the material progress that has genuinely been made distorts the task superiority of us.

The post 7 Expert Opinions I Agree With (That Most People Don’t) appeared first on Scott H Young.