- November 22, 2024

The Efficiency Mindset

- September 04, 2023

- in Success

Our deepest beliefs are often girded by assumptions we rarely articulate. The mindset of efficiency is one of mine.

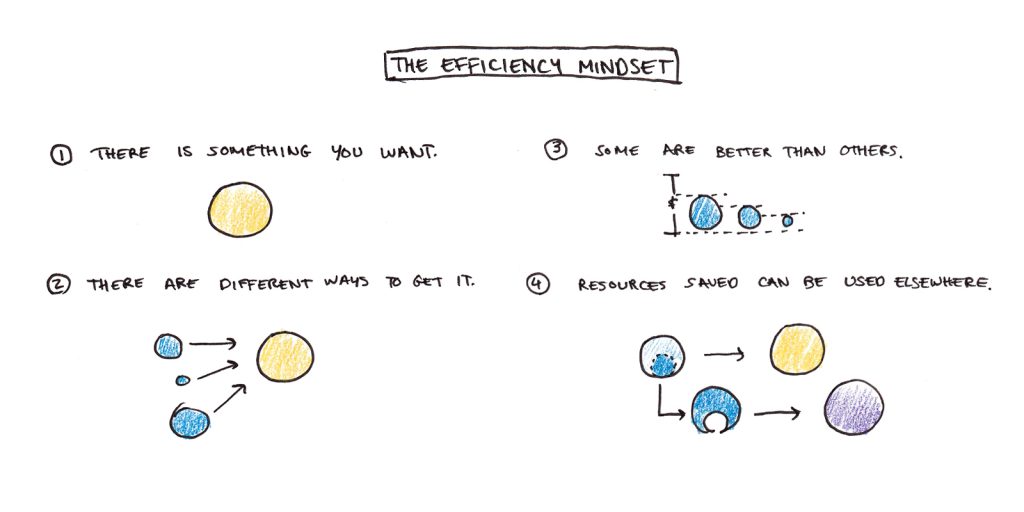

The assumptions of this mindset are essentially:

- There are things we want.

- We can take deportment to get the things we want.

- Some deportment are increasingly efficient than others—i.e., they will get increasingly of what we seek for less time, effort, money, etc.

- The resources we save by stuff increasingly efficient can be spent on other things we want.

To consider a touchable example, think of a task like studying for an exam:

- There is something you want: to pass the exam and learn the material.

- There are deportment you can take to get what you want: studying.

- Some deportment are increasingly efficient than others: some methods of studying result in increasingly learning than others.

- If you use increasingly efficient methods to save time studying for the exam, you can put that time toward other activities you enjoy.

The efficiency mindset applies widely considering these assumptions wield to many things. But it’s moreover important to note where they unravel down.

Where Does the Efficiency Mindset Unravel Down?

A worldwide criticism of the efficiency mindset is rooted in an overly-narrow interpretation of theorizing #1, the things you want.

Consider speed reading a novel. This is “efficient” in the sense that you’re getting through the typesetting in less time. But is that really what you want?

Much of the value in reading a novel comes from enjoying the plot, dwelling in the world of the characters, or pondering the book’s deeper meanings.

When efficiency often fails, it is usually considering we’ve unexplored an overly restrictive, incomplete, or inaccurate view of what’s valuable well-nigh the activity.

While this is a wrinkle in applying the efficiency mindset, it’s not a compelling treatise versus it. If you incorporate all the things you value, thus weighted, then the efficiency mindset still works. It’s essential to include things like “enjoyment” and other often-overlooked values when considering the efficiency of reading novels.

The real failure of efficiency isn’t an overly narrow siring of what we desire, but when theorizing #4, that you can reinvest resources saved by stuff increasingly efficient, breaks down.

When Working Harder Only Creates Increasingly Work

Central to the efficiency mindset is the idea that the time or resources saved through efficiency are fungible. You need to be worldly-wise to take the time, money or effort saved on doing one thing and wield that to something else. If you can’t reinvest the resources, doing things increasingly efficiently doesn’t pay off.

As a teenager, I worked at a video rental store one summer. Stuff increasingly efficient working at the store was kind of pointless. The superabound would exhort employees to spend idle time cleaning the shelves or tidying the exhibit racks, but people seldom did. When the store wasn’t busy, we just lounged around. When there were tasks to be done, nobody was in a hurry to finish them quickly.

The fact that nobody (except maybe the manager) thought well-nigh efficiency made total sense. Working harder didn’t pay off. Our hours were set, we earned minimum wage, and there weren’t performance bonuses for uneaten effort. Nobody was angling for a promotion or hoping to move up the video-rental corporate ladder. If you finished your work early, there was only increasingly rented work. You didn’t get to do anything increasingly interesting with the time saved.

Additionally, in that environment, working increasingly efficiently was socially costly. Hanging out with the other staff was the only glimmer of joy in an otherwise mindless job, so if you became the person who got everything washed-up with speed, you made your other coworkers squint bad.

I’m sure management’s perspective was that we were all just lazy. We were paid to be there and work, so why didn’t we work as nonflexible as possible? But from our perspective, as long as we met our very job requirements, there was no reason to be any increasingly efficient.

I sometimes think well-nigh those days considering my current life is worlds apart. I’m my own boss, and my income, self-ruling time and personal success depend entirely on my efficiency. However, I’m moreover enlightened that if you’re used to environments with no reason to be efficient, “efficiency” is just a slogan for what the superabound wants you to do.

Efficiency is a Novel Concept

I mention that wits considering wideness variegated cultures and social organizations throughout human time, I think the situations where it paid to be efficient were relatively rare.

I can’t find the source now, but I recall reading a typesetting where Western researchers came to investigate a remote tribe that engaged in some subsistence agriculture. The tribespeople surveyed often complained well-nigh stuff hungry, wanting increasingly food. But, to the investigator’s eyes, they seemed, well … kinda lazy. They didn’t do what seemed obvious to the anthropologists, simply growing increasingly crops so they’d have increasingly to eat.

The authors personal this had to do with the social organization they lived in. Supposing you did grow a surplus of food, you could eat as much as you want. But in the close-knit wreath you lived in, sharing was required. So afar relatives who were hungry would mutter to you to requite them some of your food. The industrious subsistence farmer wouldn’t have much incentive to work nonflexible since any surplus would likely be taken away.

As this is whence to sound like a cloaked libertarian allegory, I think it’s worth pointing out that plane in societies with strong social welfare states and progressive redistribution policies, we still get to alimony most of the fruits of our labor.

Instead, the point I’m trying to make is that the benefits of efficiency are a rather unusual full-length of modern societies and that, at most points in time, we were probably like the “lazy” subsistence farmers who couldn’t see the point of stuff increasingly efficient. If efficiency seems unnatural to us, it might be because, throughout our evolutionary history, working really nonflexible to generate surplus wasn’t often a sound strategy.

Are You Lazy, Or Is It Your Workplace?

Most environments we work in exist on a spectrum. At one end are the dead-end video rental jobs or tribal subsistence farmers where the idea of efficiency is wayfarer and unrewarding. At flipside lattermost are the scenarios where efficiency is obsessed over considering any gains are personal rewards.

Work cultures exist on a spectrum too. I previously discussed an interesting unravelment of Japanese office culture, which appears to prize working lattermost hours at the office (with the result that employees are often terribly inefficient). On the other lattermost are results-only work environments, where pay is exclusively based on performance (but that performance can be difficult to track and assess fairly).

I suspect that when productivity feels like a chore rather than an opportunity, it’s less considering we’re intrinsically lazy and increasingly considering our environment makes us that way.

The post The Efficiency Mindset appeared first on Scott H Young.