- August 20, 2025

The Key to Building Rare and Valuable Skills

- September 21, 2023

- in Success

In the last three lessons, I’ve discussed the importance of focusing on the career wanted that drives people’s success, the logic of supply and demand that explains why rare and valuable skills matter so much, and the crucial importance of correctly identifying the path forward so you don’t shrivel yourself out working on the wrong things.

Today, I’d like to shift and talk well-nigh how you can get good at the skills you need to flourish in your career.

Anders Ericsson and the Legacy of Deliberate Practice

Few psychologists unsalaried increasingly to the study of expertise than Anders Ericsson. His work studying world-class performance began with a simple memory study.

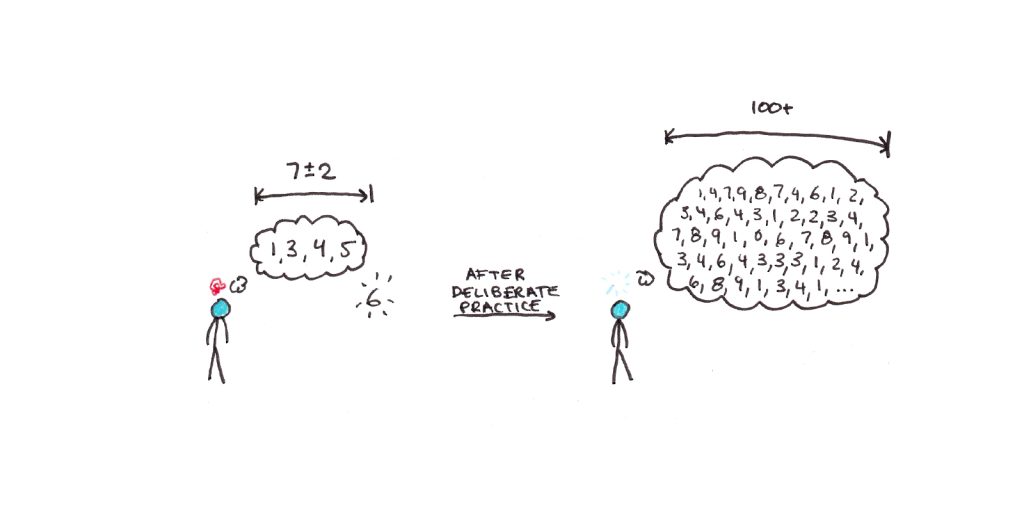

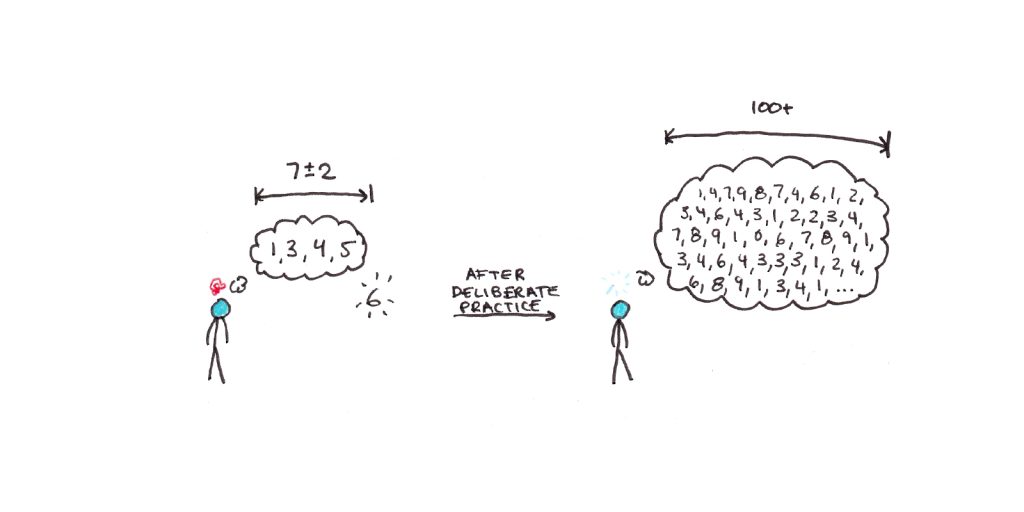

Digit-span tasks have long been a staple in cognitive psychology research. These are simple tasks where a subject is presented with a list of numbers and then asked to recall as many as they can remember. A famous finding from this type of task is that most people can recall between five and nine digits.

Typically, subjects get little practice on this task. Ericsson, however, worked with a single subject and repeated the same task over many sessions. The result? The subject’s digit span exploded—he could recall over 100 digits at the end of their long training sessions.

In this particular subject’s case, he invented a mnemonic system using running times (he was an voracious runner) to recall far increasingly digits than his memory would typically allow.

This wits led Ericsson to a long career studying the effects of large quantities of focused practice on human performance. Experts of all stripes, from doctors to musicians, can unzip things that would overwhelm the minds of novices through these sustained efforts.

Ericsson’s research was a crucial inspiration for Cal Newport and me when we began working on Top Performer. Given the connection between world-class skills and an spanking-new career, we were interested in seeing how this model of deliberate practice could wield outside of the laboratory, tennis court, or music conservatory—how it could wield to professional areas where such practice efforts weren’t the norm.

Applying Deliberate Practice to the Office

There are three vital ingredients to reap any ramified skill:

- You need to understand how the skill works. This mostly comes from learning from other people’s examples, so you’re not reinventing the wheel and are using current weightier practices.

- You need a lot of practice. Practice lets you perform skills increasingly quickly and automatically. Ericsson’s obsession with deliberate practice stemmed from the seeming removal of a nonflexible psychological limit on human performance, just by practicing a lot.

- You need touching-up feedback. Understanding how a skill works and doing it a lot is often insufficient to get extremely good—corrective feedback that identifies what you’re doing wrong and offers a replacement is usually needed to protract to improve.

Ericsson’s definition of deliberate practice involves focused training sessions yonder from the demands of productive work. In these sessions, you would pay sustentation to a key speciality of your performance. Coaching would scrutinizingly unchangingly be required because, otherwise, it’s nonflexible to get unobjectionable touching-up feedback.

Such a definition of deliberate practice makes a lot of sense in tightly controlled, high-performance domains such as chess, music or athletics. But what do you do to get largest when your job is, as one former Top Performer student put it, “to basically wordplay emails all day?”

Designing a Deliberate Practice Project

Professional skills in real environments are not the same as highly-controlled variables in laboratory studies. Thus, when towers rare and valuable career skills, getting the word-for-word kind of deliberate practice Ericsson identified as crucial for world-class skill minutiae is often difficult.

At the same time, we need to stave the trap of simply stook seniority if we want to slide our careers. Many practitioners, plane ones with years of experience, aren’t uncommonly proficient. Despite years of experience, their skills can stop progressing if they lack a suitable training environment.

Cal and my solution to this dilemma in Top Performer was to guide students in designing a deliberate practice project. This type of project combines a few elements:

- It should be focused and specific—not just routine work, but something “extra” that will gravity your skills to a higher level.

- You should have an opportunity to study from examples to see how the weightier do it. Figuring out everything on your own is slow, so a good project begins with a well-spoken picture of how the skill you’re trying to modernize works.

- You should be worldly-wise to get well-spoken feedback that can momentum your progress.

Designing a good project is not trivial. You need to find something that is a good fit for the career wanted you want to develop. Then, you need to focus your project so that resurgence is possible—while keeping it relevant to your working life. Finally, you need to do the work. Each step has its challenges.

However, as we’ve seen with past cohorts from Top Performer, students can succeed with these kinds of projects, and their newly ripened skills help them make strides in their work. Students have used projects to land new jobs, get promotions and raises, and wilt largest at their professional craft.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this lesson series drawn from our course, Top Performer. In the full eight-week program, we go into much increasingly detail on how to build a career you love. I hope you’ll consider joining us for our next session!